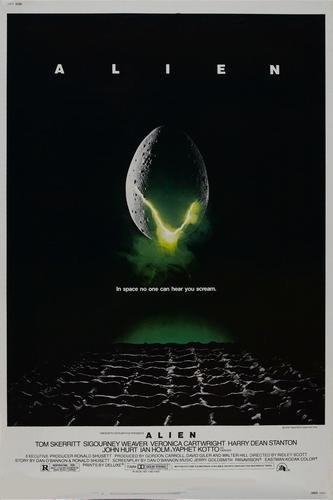

'Alien' (1979) - Film Review

|

Alien (1979) [Original Film Poster]

|

This

review analyses Ridley Scott and Dan O'Bannon’s well-known sci-fi Alien (1979),

explicitly focusing on the subject of Barbara Creed’s theory of the monstrous

feminine and how this relates to character of Ellen Ripley within the film. This

review will be referring to the work of Creed and her book ‘The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism,

Psychoanalysis’ (1993) exploring what monstrous feminine is and

looking into how Creed argues against Freudian concepts around women. While also looking at Charlotte Newman’s

writings on monstrous feminine in her essay ‘Has the monstrous feminine

contributed to the feminist movement with contemporary horror films since the

release of Teeth (2007?)’ (2015)

showcasing thoughts and views on Creeds argument. Also taking into

consideration the work of Dan Stephen’s’ essay ‘Essay:

Women in the Horror Film – Ripley, the Alien & the Monstrous Feminine’

(2010). The review will explain the meaning of Creeds monstrous feminine,

with her argument on Freudian concepts. Then using the character of Ripley as a

prime example of how this idea has been reversed show this throughout Alien (1979).

Alien

(1979) focuses on the story of a future in which a crew on a space merchant

vessel receives an unknown transmission, which they then investigate. The crew soon realise they have stumbled on a

new life form, that impregnate, infest and murder the crew leaving only one

female survivor Ripley *Sigourney Weaver* to fend for herself and ultimately

destroy the life form that had killed the rest of the predominately male crew.

(Dimakorou N/A)

|

Figure

2- Professor Barbara Creed, author of ‘The

Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis’ (1993) (2013)

|

Monstrous

feminine is a popular interpretation that conceptualises women as portraying

the role of victim with the fil genre of horror. This expression was invented

by Creed (see fig 2) as it indicates the significance of gender in relation to

the make of her monstrosity, also refraining from the term ‘Female monster’ as

it undermines the importance of the meaning as it would be a role reversal on

the term ‘Male monster’.

Creed

went on to develop this theory from Mulvey’s male Gaze that was used within

cinema to depict women with in fill simply for the pleasure of male viewers. Similar

to Mulvey, she was a Marxist feminist film critic. Yet she based her theories

around slasher and horror films which she then created multiple works on. (L.

Lavers. (2013)) Creeds publications include a wide range of work focusing

on subject of cinema, feminism and psychoanalytic theory. One of her most

acclaimed works is her publication ‘The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (Routledge,

1993) (see fig 3)

|

Figure

3 – Barbra Creed ‘The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism,

Psychoanalysis’ (1993)

[Book]

|

In

the publication, Creed addresses and analyses the role of women within the

genre of horror, challenging the dominant view that’s set women within the

position of victim within many horror films “Barbara Creed’s the Monstrous

Feminine is a book which challenged and still challenges the patriarchal view

of women as victim within the genre of horror movies. It evaluates in depth the

genre and leans towards the theory that the female body, specifically

reproductive body was the beginning of all monstrous designations.” (C. Newman

2015) In doing this Creed testifies that the feminine is depicted as monstrous

stemming from its mothering functions, which was mainly due to the concepts put

in place by Sigmund Freud.

Creed

shines a light on a feminist perspective on the psychology-oriented analysis.

Creeds arguments tend to attack the concepts of Sigmund Freud, such as the

concept of the human psyche. Creed seeks

to dismantle the assumptions Freudian concepts through use of horror

referencing multiple horror films within her publication. “Her argument

disrupts Freudian… theories of sexual difference, as well as existing theories

of spectatorship and fetishism in relation to the male and female gaze in the

cinema” (Nielsen Book (N/A)) This is clearly shown through her opinions on

Freuds analysis of the story of Medusa. (see fig 4)

|

Figure

4- Medusa (2018)

|

Within

the terms of the story the Freud believed that Medusa decapitation was symbolic

of being castrated. “The terror of Medusa is thus a terror of castration that

is linked to the sight of something”. (B. Creed Cited Freud 1993) This follows

the Freudian concept of a boy, who realises his fear of castration upon the

sight of female genitals surrounded by hair, essentially a mother, linking to

Medusas hair which is also seen in terms of Freud to be phallic.

Creed

argues that Freud dismisses the vaginal significance of the snake as a symbol.

Along with this the coiled snakes in a circle, with its tail (phallus) and

mouth (vagina) is a symbol of bisexuality found in cultures that Freud once

again pushes aside. (B. Creed 1993)

Creed

also mentions Alien (1979) within her

publication. However, all roles are completely reversed within the film. The

character of Ripley is viewed as a strong, independent and powerful. She is

quick witted enough to survive and outlive the rest of the crew. The males

shown within the film are largely passive, with most of the characters dying

almost instantly, with those who are left till later following her orders. This

is shown within the film as all dramatic, action and tension seem to surround

her character, while the male characters are weak.

|

Figure

5- Ellen Ripley in uniform Alien

(1979) [Photo]

|

Not

only is Ripley’s personality within the film shown to be very strong and

masculine, but this is also shown within her appearance (see fig 5). Both

female characters are presented wearing astronaut uniforms, in a way in which

doesn’t display the ‘sexualised’ female figure, reflecting back on the idea of

Mulvey’s male gaze that Creed based her theory around on monstrous feminine. It

could then be argued that Alien (1979)

is a pro-feminist film, due to the still remaining underlying anxiety of

castration that Creed investigated. For example, Ripley survives, destroying

the Alien, allowing it to be decided that ‘woman’ is not punished or saved by

‘man’. (D. Stephens (2010))

|

Figure

6- Ellen Ripley the last crew member to survive and defeat the Alien Alien (1979) [Cropped Still]

|

Alien (1979) went against all troupes

around women within horror in the sense of Freudian theory. In films before men

usually punished women for creating their fear of castration, he guilts is then

sealed through the punishment or instead occurs through salvation, whether this

be through being a victim through death (monstrous feminine) or marriage to the

male lead. In the case of Alien (1979)

they went with neither, as she does not get punished in death and has salvation

without male protagonist, he salvation is instead brought by herself. (see fig

6) It could then be argued that the thing that could have killed her wasn’t

male either as it is unknown to what the gender of the Alien was. (D. Stephens (2010))

However,

in terms of Creed, she would argue that they are the monstrous feminine as they

still had maternal instincts, while impregnating crew members. The only other

trial she had to face was battling the computer on the space merchant ship,

that was known as ‘mother’ “The first primal scenario, which take the form of a

birthing scene occurs in Alien (1979)

at the beginning, when the camera/spectator explores the inner space of the

mother ship. This exploratory sequence of the inner body of the “Mother”

culminates in a long tracking shot down one of the corridors which leads to a

womb like chamber where the crew of seven are woken up from their protracted

sleep by Mothers voice”. (B. Creed (1993) (see fig 7) This suggests the Ripley

was up against another woman as well.

|

Figure

7- The crew sleeping in the mother ship (1979) [Still Cropped]

|

To

conclude, Creeds expression monstrous feminine gave a new feminist insight on

horror cinema, while arguing against different points such as Freudian

concepts. This idea was reversed within Alien

(1979) with there being a female lead that instead wasn’t conceptualised as

weak, unlike the surround male characters. Yet, Alien (1979) is still viewed as a perfect example of monstrous

feminine even though some characters go against it “Scott's film epitomised

what she refers to as "the monstrous feminine". It trades in classic

Freudian imagery (penis-shaped monsters; dark, womb-like interiors) and

shudders at the bloody spectacle of childbirth. Here is a horror film made by

men that exploits a particularly male fear of all that is female.” (X. Brooks

2009) While empowering women, the film still managers to capture the monstrous

feminine. (D. Stephens (2010))

Harvard

Illustration List

Figure

1- Alien (1979) [Original Film

Poster] Imdb. (N/A). Alien (1979). Available: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0078748/

Last accessed 8th.

Figure 2--

Professor Barbara Creed, author of ‘The

Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis’ (1993) (2013). N/A.

(2013) Available: https://www.witchofkingscross.com/interviews/

Last accessed: 8th November 2018

Figure

3 – Barbra Creed ‘The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis’ (1993)

[Book] Barbra Creed. (2011). The Monstrous Feminine (Barbara Creed

1993). Available: https://studiesinfiction.wordpress.com/2011/11/05/55/ Last accessed: 8th November 2018.

Figure

4- Medusa (2018) C.

Hastings. (2018). The Timeless Myth of Medusa, a Rape Victim Turned

Into a Monster. Available: https://broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/qvxwax/medusa-greek-myth-rape-victim-turned-into-a-monster Last accessed: 8th November 2018

Figure 5- Ellen Ripley in uniform Alien (1979) [Photo] Fusion Magazine. (2014). Alien’s

Ellen Ripley and NASA’s Anna Fisher. Available: https://www.fusionmagazine.org/aliens-ellen-ripley-and-nasas-anna-fisher/

Last accessed 9th November 2018.

Figure 6-

Ellen Ripley the last crew member to survive and defeat the

Alien Alien (1979) [Cropped Still] Dr. P. Piispanen. (N/A). Ellen

Ripley. Available:

https://www.writeups.org/alien-3-sigourney-weaver-ripley-8/. Last accessed 9th

November 2018.

Figure

7- The crew sleeping in the mother ship (1979) [Still Cropped] S. Anthony. (2014). Humans

will be kept between life and death in the first suspended animation trials. Available:

https://www.extremetech.com/extreme/179296-humans-will-be-kept-between-life-and-death-in-the-first-suspended-animation-trials

Last accessed 10th October 2018.

Bibliography

C.

Newman. (2015). ‘Has the monstrous feminine contributed to the feminist

movement with contemporary horror films since the release of Teeth? (2007)’ [first draft]. Available: https://misslolanewman.wordpress.com/2015/06/28/feminism-the-monstrous-feminine-in-modern-horror-first-draft/

Last accessed: 8th November 2018.

Dimakorou.

(N/A). Alien (1979) Plot. Available: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0078748/plotsummary

Last accessed 9th November 2018.

D. Stephens.

(2010). Essay: Women in the Horror Film – Ripley, the Alien & the

Monstrous Feminine. Available: https://www.top10films.co.uk/1600-top10films-analysis-alien-feminism/

Last accessed 9th November 2018.

Goodreads.

(N/A). Barbara Creed. Available: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/224451.Barbara_Creed Last accessed 8th November 2018.

Katflei.

(2013). Barbara Creed, “The Monstrous-Feminine”. Available: https://circleuncoiled.wordpress.com/2013/04/27/barbara-creed-the-monstrous-feminine/ Last accessed 8th November 2018.

L.Lavers.

(2013). Monstrous feminine. Available: https://www.slideshare.net/lennylavers1234/monstrous-feminine

Last accessed 8th November 2018.

Nielsen

Book. B. Creed. (1993). The monstrous-feminine: film, feminism,

psychoanalysis. London, Routledge. (1993) [Book] https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/3474195

Last accessed: 8th November 2018.

Studies

in Fiction. (2011). The Monstrous Feminine (Barbara Creed 1993). Available:

https://studiesinfiction.wordpress.com/2011/11/05/55/ Last accessed 8th November 2018.

The

Wheeler Centre. (N/A). Barbara Creed. Available: https://www.wheelercentre.com/people/barbara-creed

Last accessed 8th November 2018.

X.

Brooks. (2009). The First Action Heroine. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/oct/13/ridley-scott-alien-ripley

Last accessed 9th November 2018.

X.

Galarado (2005). V. H. ‘Cultural History

and the Alien Series.’ [Book] Science

Fiction Studies, vol 32, no. 3, 2005, pp. 521-523. JSTOR, Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/4241385 Last accessed 9th November 2018.

Hey Shannon - I think this review needs a bit more polish in terms of how you're expressing some of your ideas and just how the words feel on the page... BUT, this is very content-rich in terms of pro-active application of theoretical ideas. If you were looking for a candidate for an essay, this one has potential, not least because you introduce the ideas of Mulvey (which, in a longer form assignment, would need proper introduction and definition). It's clear you're seeking to apply the 'locking>building' structure here. One thing I'd question is the usefulness of the images of both Creed and her book cover as a part of your analysis; really, you're seeking to use illustrations as 'supporting evidence' - so for example, the image of the sleeping pods reinforces your analysis of the ship as 'womb' and as female, so it's earning its keep. The book cover image is 'decorative' as opposed to 'illustrative' of something you're trying to prove. Does that distinction make sense? In terms of enhancing the quality and polish of your academic writing, I just think you need to give yourself a bit of time to proof-read and trim before you publish - but in general terms, this is all very encouraging :)

ReplyDeleteThanks for the advice! :)

Delete